Issue 127

Term 4 2023

Unheard Voices: Transforming library spine labels for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation

Robyn Ellis worked with her colleague, Aboriginal man Eli Pietens to create an informative and respectful spine label system for their school community.

The need for change

Robyn Ellis, a dedicated teacher librarian at Byron Bay High School, found herself facing a challenging task. Teachers were turning to her, seeking young adult fiction that aligned with the increased focus on the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the new K–10 English syllabus. As a professional dedicated to fostering an inclusive educational environment, she was eager to help but faced a dilemma.

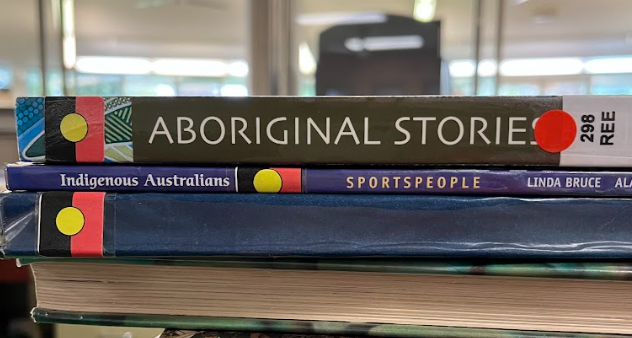

Her school library had already adopted a symbolic gesture of inclusivity before she had started working there – an Aboriginal Flag sticker placed on the spines of books that covered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content. However, this well-intentioned sticker had its shortcomings. It did little to provide context or advice on how each stickered book’s content reflected the perspectives and history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This left teachers unsure of the integrity of the resources they were wanting to incorporate into their teaching.

‘It was really a “catch-all” for everything, from author to themes to maybe artwork, and so it was used pretty indiscriminately. It was worrying me that it wasn’t really clear what this sticker meant,’ Robyn observed. She resolved to find a more nuanced solution. An idea came when she attended a School Library Association of New South Wales (SLANSW) professional learning online meet-up, focused on the role of libraries to incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices into the English curriculum. This virtual session introduced her to a transformative resource – the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) guide to evaluating and selecting educational resources.

The AIATSIS guide offers a structured approach to evaluating materials with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content, grounded in principles of respect for authorship, perspectives and partnership. It classifies resources into five distinct categories, each providing educators with insights into the level of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice and participation.

- By mob: Resources developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- With mob: Developed in respectful partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- For mob: Developed on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- About mob: Resources with no Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander input, support or partnerships.

- Against mob: Resources that portray deficit or racist views.

With this guidance and a deeper understanding of the nuances of representation, Robyn returned to her library. Her mission: to overhaul the spine labels, transforming them into something more thoughtful and respectful. She began by heeding a fundamental lesson she learned at the SLANSW meet-up: engaging with the local Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community was paramount when finding solutions to such challenges. Although Robyn had few personal connections within the local communities, a valuable resource lay within her own school – a First Nations committee comprised of dedicated teacher-members.

A photo of the spine labels Robyn Ellis inherited at her school library.

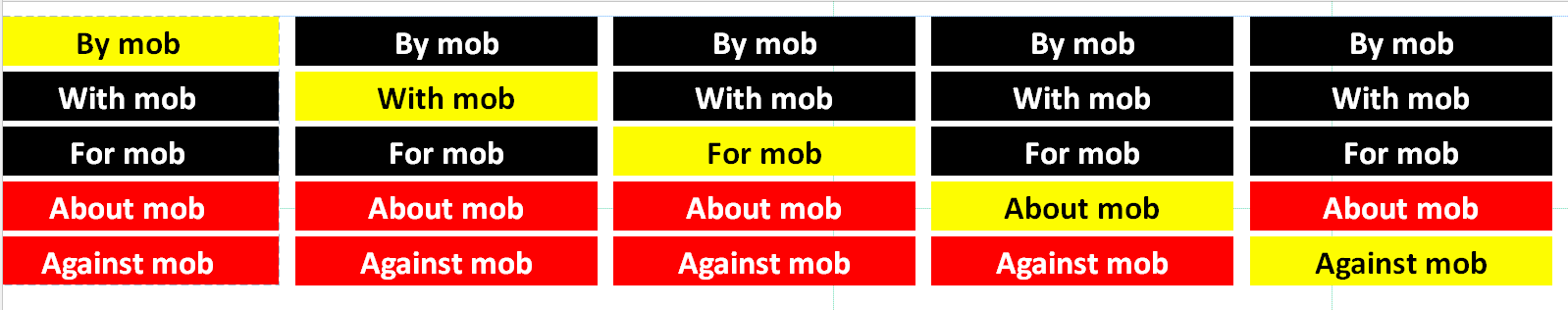

Examples of the spine labels created by Eli and Robyn (yellow indicates the resource classification).

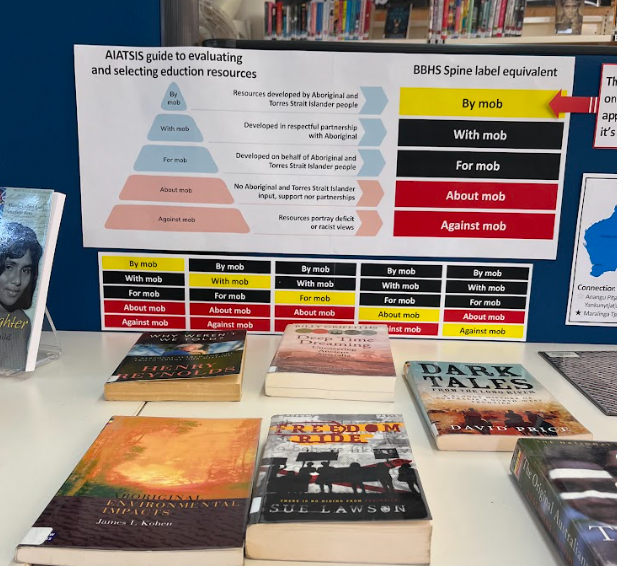

A book display created using the new spine labels, with advice for the school community covering the meaning of each classification.

The committee pointed Robyn to Eli Pietens, an English teacher at Byron Bay High School. Eli’s passion for literature and his Aboriginal heritage made him an excellent collaborator for the project.

Robyn approached Eli with her vision. As Eli tells it, his response was immediate. ‘I love literature and I love my culture, so when this project presented itself, I was all in.’

Working together for greater respect

Over the course of several months, Robyn and Eli embarked on a collaborative journey to transform the library’s spine labels. During the course of their work, they cultivated a bond and realised that there was a symbiosis between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and the role of library staff in schools.

Eli, reflecting on the experience, shared his perspective. ‘In Indigenous cultures, narratives and stories are central to the way we keep culture. We’re about preservation of what was, about exploration of new ideas. There are many overlaps between librarians. I’ve found it a very easy relationship to find positivity in.’

To bring the labels to fruition, Eli and Robyn enlisted a staff member with a background in graphic design. This collaboration resulted in a final design that was both easy to understand and culturally respectful.

Each label bears the colours of the Aboriginal flag and lists all the AIATSIS classifications, with the chosen classification for each book highlighted in yellow.

As the number of resources with new spine labels has grown, Robyn has found it considerably easier to curate reading lists in her library catalogue and create book displays for her school community. The labels have also boosted her confidence in recommending resources to teachers, helping to address the initial problem she faced when asked for young adult fiction covering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Perhaps the most challenging of all classification tasks still remains: creating a list under the ‘against mob’ classification. This involves identifying resources that portray deficit or historically racist views, signalling their outdated nature.

Robyn is undeterred by the complexity of this task, and firmly believes it to be an essential component of the project. In her own words, ‘I think we have to make an against mob list.’

For her, this seems a vital step in educating her school community about the characteristics of resources falling under this classification and fostering a critical awareness of historical biases.

The importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices in libraries

The spine label project undertaken by Eli and Robyn serves as a vivid example of how libraries are hubs for cultural change that can help shape and reshape the educational landscape. It also exemplifies how library staff across Australia can play a pivotal role in amplifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices within their educational institutions.

However, while there is great potential for change, many schools remain hesitant to embark on projects like the one Eli and Robyn have championed. Fear of making mistakes can stifle progress. Eli offers a perspective to combat this fear, emphasising that the journey of change is ongoing.

‘The best way to combat that feeling or belief is [to acknowledge] that it’s an ongoing process,’ Eli advises. He encourages embracing feedback of any type as a sign of active engagement with the system, a testament to the work being done.

Eli outlines some practical steps for those looking to initiate similar projects. He suggests starting by quantifying the resources needing attention in the library, and then consulting with the school community to help understand what will be required for the project.

Although projects like these can seem onerous at the outset, breaking them into smaller chunks or activities, such as those suggested by the project team in this article, can help them feel more achievable in the long run.

Additionally, he underscores the importance of reaching out to local groups, such as the Aboriginal Education Consultative Group (AECG), as vital partners in the journey toward a more inclusive and culturally sensitive educational experience. While the AECG is based in New South Wales, there are many similar groups in other states, as well as local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups that can be approached.

Spine labels such as those created by Eli and Robyn are more than just markers – they are symbols of a shift towards a more inclusive and culturally sensitive educational experience for the school community. Eli and Robyn’s unwavering determination to press on with this challenging but crucial task underscores their commitment to reshaping the educational landscape, one label at a time.

Thanks to Robyn Ellis and Eli Pietens for their participation in the creation of this article.

References

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). (2022). AIATSIS Guide for evaluating and selecting educational resources. AIATSIS: Canberra. Retrieved from https://aiatsis.gov.au/ education/guide-evaluating-and-selectingeducation- resources

NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA). (2023). English K–10 Syllabus. Retrieved from https://educationstandards. nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/learningareas/ english-year-10/english-k-10