Issue 107

Term 4 2018

All together now: recognising the work of all school library staff

Karys McEwen writes about the importance of being inclusive in our advocacy for school libraries.

There’s no doubt that school libraries in Australia are facing challenges. You only have to pick up a professional publication or attend a conference to hear the widespread discussion about how shrinking budgets and staffing cuts are affecting the industry. But amid all the debate, school library staff are working hard to show how valuable they are to the communities they service. There are countless ways in which we are proving to be resilient.

However, there is one key thing missing from the conversations that take place in library journals, at professional development days, or in email chains where colleagues from across the country share ideas on how to keep school libraries funded and thriving: in order to persevere, we need to recognise that we are stronger together, not divided. We need to go into battle for each other.

Among the most important factors to consider is how school library staffing is changing. Up until a few years ago, the teacher librarian role was more prevalent in school libraries. Nowadays, there are primary and secondary libraries that are run by librarians or library technicians. However, there are also some instances where libraries are being managed by those without any library qualifications at all, or they are completely unstaffed. More troubling are those schools without libraries at all. As a profession, we should always advocate that, at the very least, every school needs a library. We should also never lose sight of how valuable qualified library staff are to a school community.

How many times have you heard a librarian describe themselves as ‘just’ a librarian? I am personally guilty of this — not because I am ashamed of my position title, but because I am well aware of the stigma that is sometimes attached to non-teaching staff. As the library manager in a secondary school where there hasn’t been a teacher librarian for nearly a decade, there have been times where I have felt looked down upon by people both from within my school and from within the wider industry. Fortunately, attitudes are beginning to change.

When it comes to secondary schools in particular, it is not always essential to have a teacher librarian running the library. Miffy Farquharson, Head of Libraries at Woodleigh School, describes one school in Melbourne that has appointed a librarian as the manager, keeping their teacher librarians for teaching. ‘It seems to work reasonably well, and has freed the teachers from the management side, whilst keeping the library systems working smoothly,’ she says. ‘The staff know what they are and are not responsible for and there is room for discussion within the team.’

This set-up has also been working successfully in other schools across Australia. Of course, it is always up to the individual school to appoint the right staff for their library, and allow the team to adapt as needed. Sue Osborne, Head of Library at Haileybury Brighton, argues that qualifications in collection curation and development, as well as a deep knowledge of literature trends, is vital. ‘Librarians can always instruct on the use of library resources — they do it in a public and specialist setting all the time — and there is no need for teachers for that,’ she says. ‘While it is important to have knowledge of curriculum and methods of instruction used in schools, information management expertise is the most important thing.’

Ruth Woolven, Librarian at Kew Primary School, says that ‘if a school cannot have or chooses not have a teacher librarian, then a librarian will still work with teachers towards delivering a program that complements the curriculum’.

While nobody in the library world would actively argue against having teacher librarians in schools, sometimes in the fight to preserve these positions that are currently being eroded, advocates can fail to focus enough on the wide and vital roles of other staff and, in particular, the loss of qualified library staff in schools.

‘School library advocacy groups are mostly represented by teacher librarians and schools from the independent and Catholic sectors. I absolutely applaud the work they do and I completely understand their view on maintaining the best practice of having a teacher librarian,’ Woolven says. ‘However, I do think it has the potential to impede the school library sector if there is not equal consideration given to the other models being used, particularly in the public sector. If the only focus is on the erosion of teacher librarians, many other very capable library staff may be unsupported.’

I was recently in communication with an author who is a strong advocate for school libraries. During our conversation, they acknowledged, with apology, that their advocacy had often focused on teacher librarians, who they had erroneously equated with qualified library staff. The author realised how this seemingly insignificant use of language could dismiss the work of other staff within the library, and promised that future advocacy on their part would always be broadened to all qualified school library staff.

Semantics are important, and inclusive language is the first step towards positive change. The School Library Association of Victoria recently released a new edition of ‘What a School Library Can Do For You’. This document was reworked in order to expand the focus to school library teams rather than just the teacher librarian. These updates better reflect the diversity of roles in school libraries, and this inclusivity goes a long way towards recognising the contribution of all school library staff.

Similarly, several industry bodies, such as the Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA), have now begun using the term ‘school library staff’ when advertising their professional development. This is especially significant because it has been reported that some school library staff would not be permitted by their school’s leadership to attend a conference or workshop that appeared to be explicitly aimed at teacher librarians. Farquharson says that ‘providers of library PD should be aware that many schools do employ librarians and library technicians to fill a role that would have previously been filled by a teacher librarian. Very often those staff feel isolated enough by their school situation without the industry dissing their efforts’.

For Osborne, language is everything: ‘The way staff are addressed is important because everyone working in school libraries wants to feel that their contribution is valued.’

This kind of inclusion goes beyond the library and into the whole school setting. Woolven says: ‘Within my own school context, I prefer the use of the word “staff” when referring to matters that involve all teachers and education support staff, rather than everyone being referred to as teachers. This may sound churlish but I want to feel recognised and included as much as the next person’.

In my first year working as the library assistant in a school, I certainly experienced isolation from the wider industry. Staying on the outer is an easy mistake to make: school library staff don’t necessarily have the time, energy or budget to reach out to similar schools, attend conferences, or even participate in social media. When you are not a teacher, the problem is compounded. It is hard to feel a part of the discussion if presentations and articles are geared towards those with a teaching background. Osborne says that thankfully the emphasis is shifting towards inclusivity. ‘More inclusive language has started being used by the school library sector in general,’ she says.

We need to continue on this path in order to keep all library staff in the know. When we connect with our colleagues it is easier to understand how differently each workplace is managed and run. It can also be validating, especially for those school library staff who feel that they are on the periphery because they are not teacher librarians. Even someone working in a school library without qualifications should be encouraged to skill up and feel a part of the industry.

The next step moves beyond language and is about taking action towards inclusivity, which can be done in ways both big and small. These include diversifying conference sessions so that participants can get value from the information despite their role, or opening up awards and grants to those without teaching qualifications.

The way we talk about school libraries, the way we run them, and ultimately the way we fight for them, is evolving. School libraries, as well as the associations and other bodies that support them, should continue to keep up with change and correctly reflect the industry. The movement should come from a grassroots level, too — library assistants, officers, technicians, librarians, teachers, managers and everyone in between. We need to keep working to ensure our students and their communities are resourced, safe and engaged. Let’s do it together.

Image credit

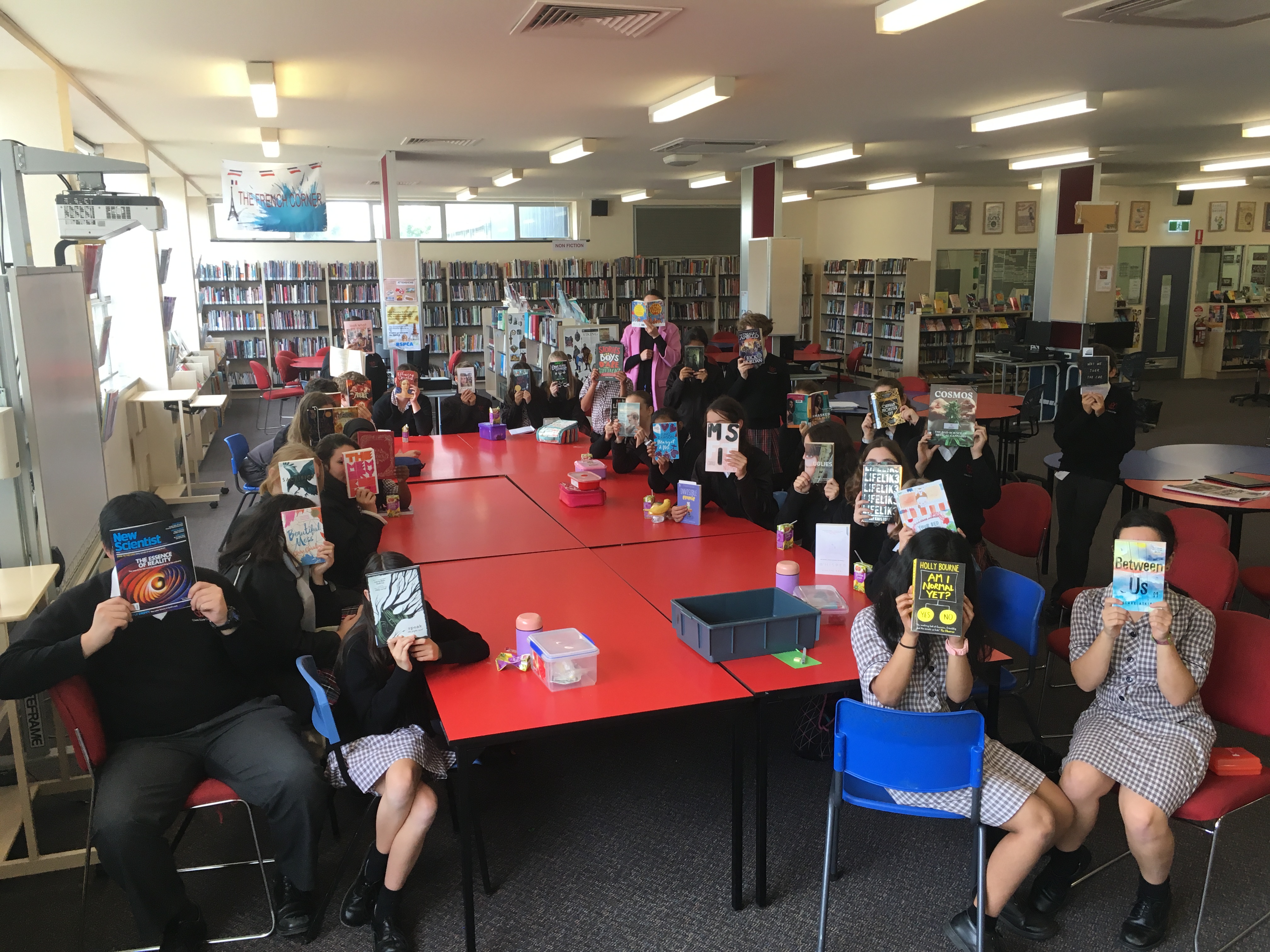

Photo supplied by Karys McEwen