Issue 92

Term 1 2015

The fourth age of libraries

Sean McMullen a Science Fiction writer and PhD in medieval fantasy literature wonders if libraries will still exist in twenty years after having got this far.

My novel, Souls in the Great Machine, (1999) involves a caste of librarians ruling a post-apocalyptic Australia, two thousand years in the future. They wear stylish uniforms and cloaks, and settle disputes by duels to the death with flintlock pistols. After it was published, I soon found myself heavily in demand as a speaker at events for modern librarians, some of whom even turned up in costumes based off my work. Fifteen years later, many of these librarians are now wondering if libraries will still exist in twenty years, let alone two thousand.

The past holds some clues about the future of libraries. What did people do for entertainment in the Dark Ages? Outside the monastic libraries there were very few books but there were bards and minstrels. Their chansons de geste, 'songs of deeds', were generally about warriors heroically slashing at each other with swords, and very little else. Then, around 1150 CE, the courtly love story, the roman courtois, appeared. These stories were by contemporary authors, and featured romance as well as battles. Being books, they could be accessed anywhere, any time, so one did not need a bard to experience the tale. Predictably, they were an instant hit, and wealthy nobles built up small private libraries of these expensive, handwritten ancestors of the novel. For everyone else, the bards continued to perform.

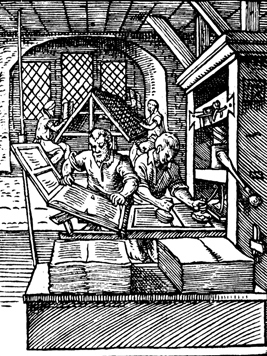

For three centuries scribes did very well, making copies of these romances by hand, but then Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press and the Printing Revolution began. This caught on about as fast as the roman courtois, and even the middle classes could afford the new mass-produced books. Within fifty years libraries were bigger, and librarians were vital in keeping collections in order, preventing theft, and helping users find what they wanted. The scribes were out of a job.

Another three hundred years passed, then the Nineteenth Century saw the next stage of the modern library commence. Education for the masses led to public libraries, mechanics institute libraries, and school libraries. Far more people could now read, and they all wanted books. Books began to be produced cheaply, on an industrial scale, and librarians became indispensable for cataloguing, storing, and retrieving titles within much larger libraries.

Souls in the Great Machine by Sean McMullen

Two centuries later, the Internet is now leading the biggest information expansion in history and has ended the dominance of the printed book. Electronic books cost virtually nothing to publish, store, and transport, while also being very cheap to purchase. Many are available for free. Librarians and publishers should not be worried that the birth of the internet means that the age of the library as an information warehouse is coming to an end, for librarians it is just another change in their job statement.

Imagine yourself standing on the shore of an ocean filled with information instead of water. You notice something strange about the horizon, then realise that it's a tsunami of information rushing towards you with the speed of an executive jet. That is the six exabytes (six billion gigabytes) of information that is being added to the world's databases every day. The sum of all human knowledge was one exabyte in 2003, so this digital tsunami is very big and is growing rapidly. Running will not help, and there is nowhere to hide.

Now you see a couple of people nearby with iPads. They say "Are you looking for somewhere safe?" and naturally you reply "Yes!" They say "Well, get behind us, because we're librarians and we know how to control that thing." Recently, for a story that I was writing, I researched intelligence in crows. So my first stop was to type 'intelligence and crows' into Google. I was instantly offered 8,180,000 links. At 5 seconds per hit, working 12 hours per day, it would take about two and a half years to check them all. Everyone can surf the Internet, but librarians can do it effectively. Since I am more interested in using information than finding it, I will continue asking librarians for help.

Woodcut depicting an early printing press in operation, Jost Amman c1568.

Another feature of libraries that will keep them in demand is that they can be entered, touched, and experienced. Consider Comic-Con, the huge multi-genre entertainment media convention held annually in San Diego, California. It draws 130,000 members, and tickets sell out in ninety minutes. With the Internet, the films, TV shows, and interviews with stars at Comic-Con can all be seen at home, so why are so many people going to so much trouble and expense to attend the event in person? It's because they will be part of something big, real, and exciting. They can meet the stars of their favourite shows, attend panels where directors and authors talk about things that are not yet on the internet, and have their photo taken as they ask George R. R. Martin not to kill off their favourite character from Game of Thrones.

The local library is not in this class–or is it? For young children who are learning to read, it is such a magical world filled with real things. They are not confined to a screen, instead they can browse through stories made solid on the shelves. This solidity is important. What do children do when they find a story they really love? They ask you to buy them the book, and they treasure it as something to be loved, alongside their teddy bear. When I do signings I keep getting this message from readers: real books make stories more real.

Recently I was asked to review a novel set in ancient Greece. I did not know that the publisher was a vanity press service. The plot was so far off the planet that you would have to wear a space suit to read it, but the style was even more distressing. Two of the more memorable quotes were "Hey you guys, let's get outa here!" and "Yo dudes, where's the action?" Although sorely tempted, I did not do the review. This is an example of publishing without quality control, and there is a lot of it happening. In 2012 there were 391,000 ISBNs issued for self-published titles. Publishers provide quality control for the books they publish, and librarians do it again before they let those books into their libraries. The library is a safe place, but step outside and the information tsunami is there, and it is as dangerous as ever.

All of this is an exceedingly good reason to get yourselves and your children into libraries. Continual exposure to good writing develops a good writing style, and good writing is the key to communicating effectively and getting one's message across in the digital age–with its shrinking attention spans and exabytes of competing information. If you want your children to have an edge as adults, get them into libraries now. If you are finding the Internet overwhelming, speak to a librarian. There are too many bewildered parents out there trying to cope with too much information, and wondering why their children can't tell a story, or even write a coherent sentence. Libraries and librarians can do something about that, and they do it for free. Like the lifeboats on the Titanic, we can cut back on them, but it would be a very bad idea.

The Burning Sea by Paul Collins and Sean McMullen

Image credits

- Woodcut depicting an early printing press in operation, Jost Amman c1568. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

- Souls in the Great Machine by Sean McMullen. Cover art by John Harris. Used with permission of the author.

- The Burning Sea by Paul Collins and Sean McMullen. Cover art by Marc McBride. Used with permission of Ford Street Publishing.