Issue 97

Term 2 2016

Library makerspaces: revolution or evolution?

Jackie Child and Megan Daley, librarians at St Aidan’s Anglican School for Girls, are using their makerspace to encourage tinkering and making in their school. Chris Harte talks to them about how they developed their makerspace, starting with small projects and building from there.

The makerspace movement is gaining momentum in the world of libraries, although it is not an entirely new concept. One of the first makerspaces built specifically to invigorate the hearts, hands, and minds of young inventors opened in 1876. Established by Thomas Edison in the New Jersey hamlet of Menlo Park, this space would become known as the ‘Invention Factory’.

From the Invention Factory came the phonograph, a long-lasting filament for an incandescent light bulb, an electric train, and the plans to bring electricity to cities from central generators. This place was brimming with experimentation, hard work, failure, genius, and play. The workers — or ‘muckers’ as they were known — poured time and energy into their work, going far beyond the factory model of nine-to-five labour, motivated by their immense passion for learning, inventing, and making the world a better place. Within six years, Thomas Edison had filed 400 patents, and many of these inventions have shaped our world today.

We can find modern versions of the Invention Factory at Google's X-Lab, MIT’s Media Lab, and in a growing number of library makerspaces around Australia where people are encouraged to learn by tinkering, building, experimenting, and collaborating.

School libraries are continuing to evolve from the outdated notion that they are simply repositories of knowledge stored within the bound pages of books. While the printed word may always remain the beating heart of school libraries, the dynamism of taking that knowledge, playing with it, and building something new is engaging the tinkerers of Generation Z.

One such makerspace resides at St Aidan’s Anglican Girls’ School in Corinda, Queensland, which was the recipient of Australia’s Favourite School Library in 2014. Teacher librarians Jackie Child and Megan Daley established a space to provide their students with authentic problems to solve, and the tools required to solve them.

Jackie started out with a code club, but inspired by the founder of Make Magazine, Dale Dougherty, she decided to introduce the concept of hands-on learning to the students. Jackie recalls, ‘I used a Beano Annual and a roller skate to create my own skateboard, but many children now consume, throw away and buy new things. I wanted to help fix this, to bring in sustainability, creativity and problem solving.’ Jackie proposed the idea of combining the library space with resources and technology to create a makerspace. With the principal’s full support and her fellow teacher librarian on board, the adventure began.

‘With the ability to access materials through online databases for research, we were able to reduce the number of non-fiction books we held in print, removed some of the shelves and sent the books to good homes, bought some materials, and started the makerspace,’ Jackie explains. One of the early maker projects used Elizabeth Matthews’ book Different like Coco as a starting point for the students to create marble runs; a very hands-on approach to combining building and learning to create a game. The students were then given the freedom to choose their own book and build their own marble run.

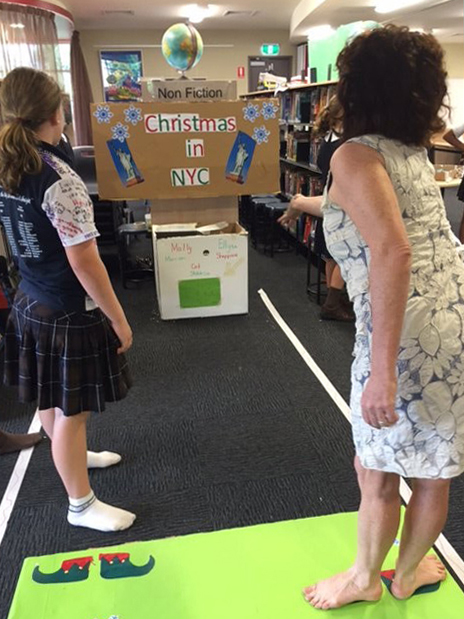

A cardboard arcade game made in the school library's makerspace

This freedom to choose is one of the things that distinguish makerspaces from traditional curriculum-driven classrooms. Jackie points out that ‘in contrast to a crowded curriculum, learning in the makerspace has no formal assessment and is simply full of joy’. The outcomes for makerspaces are driven not by standards, curriculum, and in-case learning, but by curiosity, authentic problem solving, and in-time learning. One student wanted to create a cat’s cradle as part of her maker project, and instead of waiting for it to pop up on a unit plan, she jumped online, found a video tutorial, and taught herself.

Inspired by the wonderful story of Caine’s Arcade — which is, in many ways, the ultimate maker project — Jackie and Megan helped to bring the geography and history curriculum into their makerspace, challenging students to build their own cardboard arcade games. The students built these games using the information they had learned about in class, with the intent of teaching players about different countries.

While the incredibly positive outcomes are self-evident, one may assume that creating a makerspace is an arduous and resource-heavy undertaking, but Jackie and Megan started small and allowed it to expand from there. They began with simple, low-tech projects that engendered the maker spirit, such as using copper tape to make circuits and light-up greetings cards, or having the prep students make beds for their teddy bears. One prep student in particular was exploding with pride when she presented the light cord she had built into her teddy bear’s bed design.

Jackie and Megan are now running more projects with specific resources like Lego Mindstorm robots, 3D doodler pens and 3D printing, which they do by using a printer from the high school to design and print 3D Minecraft avatars. 3D printing technology is becoming more accessible, with some robust printers selling at $500 and under in commercial outlets. Moreover, Jackie has noticed a whole new consumer trend in the 18 months since creating their makerspace, with the big supermarkets starting to sell affordable maker kits as toys.

Despite having some specialist equipment, Jackie and Megan are rekindling the sustainability values of the ‘frugal generation’ by encouraging their students to scavenge, reuse, repurpose, and upcycle the materials they have.

As with anything educators organise for learners — especially in the hands-on environment of makerspaces — health and safety is essential. Developing a respectful environment, and highlighting potential dangers such as small batteries being handled by young children, is a key part of the learning.

During the Grandparent’s Liturgy, students’ grandparents were invited to come into the makerspace to celebrate their grandchildren’s learning. Jackie and Megan set up a number of activities for the grandparents, including vibrobots, scribble machines, circuit cards, and squishy conductive dough. The grandparents were fully engaged in learning with their granddaughters; one grandparent even asked for a soldering iron when he spotted a loose wire connection, demonstrating his keen enthusiasm to get involved. What a wonderful way to engage the wider community with the school, the library, the makerspace, and their own children’s creativity, problem solving, and learning.

Student and grandfather working with conductive dough at the Grandparent's Liturgy

The conductive squishy dough was also used in a project where students built light-up models to represent characters from Glenda Millard’s beautiful book The Duck and the Darklings. Jackie and Megan shared this experience via Twitter, and AnnMarie Thomas — a professor at the University of St Thomas whose TED Talk prompted the interest in the conductive dough — tweeted back, saying what a wonderful idea it was, and shared it with her followers. This is a great example of our young makers creating global connections.

What is next for this dynamic teacher librarian duo? ‘We would love to have more concentrated time’, Jackie says. ‘Perhaps bring a Genius Hour of dedicated maker time into the timetable. We are going to put on a before-school club to give the girls more [maker] time. We are also very excited that we are able to expand our makerspace to include our own 3D printer.’

Students collaborating during the junior school's Hour of Code

Makerspaces provide students with the opportunity to learn a range of skills and meet a number of curriculum objectives, including digital technologies and computational thinking, coding, mathematics, humanities, the arts, prototyping, and engineering — just to name a few. All of the core skills, knowledge, understanding, and mindsets that we consider key to our children’s success can also be found and learnt in a makerspace; students can learn resilience, as well as gain skills in problem solving, teamwork, and communication.

Jackie and Megan explain that there is a truly holistic element to the learning that happens in a makerspace: ‘Purpose. There is genuine joy, determination and persistence in the makerspace. If a child has to solve a problem using maths to make a machine turn at right angles, they will [take risks, and] they will persist to achieve their goal. As Mitch Resnick [the Director of the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab] says, kids don’t ask to learn about variables in coding, but if they build a game where they need to keep score, they learn about variables.’

Jackie and Megan have an old Chinese proverb visible across their library makerspace — ‘I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand’ — highlighting the active nature of learning in makerspaces.

If you would like to read more about Jackie and Megan’s work, you can head over to Jackie’s blog and Megan’s blog, or you can connect with them on Twitter: @jackie_child and @daleyreads.

Interested in creating your own makerspace? Keep an eye out for the Digital Technologies Hub, to be published later this year, which will provide information about makerspaces and more. Funded by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training, the hub is designed to support the Australian Curriculum: Digital Technologies for Australian teachers, students and parents.

Image credits

Jackie Child. Used with permission.