Issue 99

Term 4 2016

An inquiry-based approach to exploring Australian history

Author Deborah Abela researched her family’s history and Maltese migrant history before writing her novel, Teresa: A New Australian. Deborah’s process can assist students undertaking historical inquiry.

In the last few years, we have witnessed the largest movement of people since World War II, and both periods resonate with themes of fear, persecution, escape, identity, and hope. This made me think of my own family’s history and how, when my father was a young boy, he left his war-ravaged home of Malta with his family for a new life in Australia. I wondered how it felt to be under siege, to have your country destroyed before your eyes, and then to leave for a new life in a country far away.

These thoughts formed the beginnings of Teresa: A New Australian (Scholastic 2016), a novel about a young girl’s post-war migration to Australia after the devastation of World War II. I wanted the novel to not only focus on my family’s story, but also on the story of the many Australians who share a similar history.

Backstory and historical context

My father was born in a cave in Malta in 1942. Lying between the battlefields of Europe and North Africa, Malta was highly prized by Hitler and remained under siege for three years, making it one of the most heavily bombed places of World War II.

After the war Malta was in ruins, and like many other Europeans, the Maltese people migrated to countries that offered the chance of a new life. They left loved ones, homes, and families behind to take a chance on an unknown future. My father, along with one million others, made the journey to Australia.

Work in Australia was plentiful, and many migrants held multiple jobs so that they could buy homes and give their children a good education. They gave up so much to create a better future for their families.

But Australia wasn’t always an easy place for them to be. The newly appointed Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, knew that Australia needed a bigger population in order to build the nation and to defend itself in the event of another war. With only seven million people, he declared that the country needed to ‘populate or perish’, but the White Australia Policy meant Australia wasn’t always welcoming of the new arrivals. My dad was picked on, bullied, and subjected to racial taunts — not only by other kids, but by adults and teachers, too.

When Australian officials interviewed potential new migrants, they wanted applicants who were healthy and of good character — but they also wanted those who were white. The Maltese knew this, so before their interviews, many women wore scarves to protect their skin from tanning, and ironed their hair straight so officials wouldn’t assume they were from Africa.

When I was a little girl, my father told me about his time in Malta. His story of being born in a cave was always my favourite. When I learned more about the bombing raids, the caves that the Maltese built to hide from German bombings, and his journey by ship to Australia, I knew it would make a fascinating story for younger readers.

Reading Teresa as a study for historical inquiry

I used inquiry-based methods to learn more about my family's past, as well as the lives of Maltese who embarked on similar journeys to Australia. Research undertaken to create Teresa included:

- My own family’s story

- Archival news footage, radio broadcasts and broadsheets

- Diaries and journals from the war and post-war period

- Historical non-fiction

- Aural history from members of the Maltese community

- Visiting Malta.

Personal history

My investigation began with my own family. I asked gentle, probing questions about their experience of the war and journeying to Australia, mostly as small children. I wanted to know what they experienced and remembered but also how they felt, so I could use these experiences to create my characters’ lives. I was very careful to insist that if something was too painful to recall, they didn’t have to tell me. Some questions that I asked included:

- What was it like growing up in Malta? (I left this question open, so they could discuss family, neighbours, school, food, their village. I wanted the choice to be theirs.)

- What do you remember of the war in Malta, and how it affected your life and the life of those around you?

- Was it hard to make the decision to leave Malta? Was Australia your only choice?

- What was the process you went through to apply for passage to Australia?

- How were you treated when you arrived?

Primary sources

I then broadened my research to investigate primary sources, including archival news footage, radio broadcasts and newspapers from the time, and war diaries and journals from soldiers and nurses both from the war and post-war period. I found a number of organisations and their websites extremely helpful, such as the National Archives of Australia’s Destination: Australia website, which was filled with post-war migrant stories.

Trove, another website developed by the National Library of Australia, is a brilliant resource to access information from sources such as books, digitised newspapers, photos, journals, and letters. This was particularly wonderful for discovering what kind of Australia migrants from the ‘50s faced. Not only politically, but also smaller details such as what brands of tea they drank, shoes they wore, and public transport they used. Through Trove, I found many digitised newspaper articles that not only reported on the new arrivals, but also indicated how the 'New Australians' were greeted.

I was very lucky in that during and after World War II, the world embraced new media and advances in communications. War journalism had improved greatly since World War I, which meant I was able to listen to radio broadcasts, and play newsreels of the dogfights in the skies over Malta. British Pathé is a wonderful site with news footage broadcast during the war. I saw videos and images of Maltese people fleeing the bombs, hiding in the caves, and struggling to survive the onslaught of the war.

There were also diaries and websites devoted to the many people who migrated after the war, with first-hand recollections of the war and of their arrival in their newfound homes.

These sites allowed me to access a mix of not only personal views of the war, but also of how the broader media and world were reporting on and viewing this period.

Secondary sources

I read historical non-fiction to add to my growing understanding of the period. This enabled me to use historical facts and dates to ensure the novel’s timeline was accurate. I found Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege 1940–1943, by historian James Holland, particularly useful. Non-fiction sources helped to add a sense of truth to the foundation of the story, but it was the personal stories that brought the novel to life.

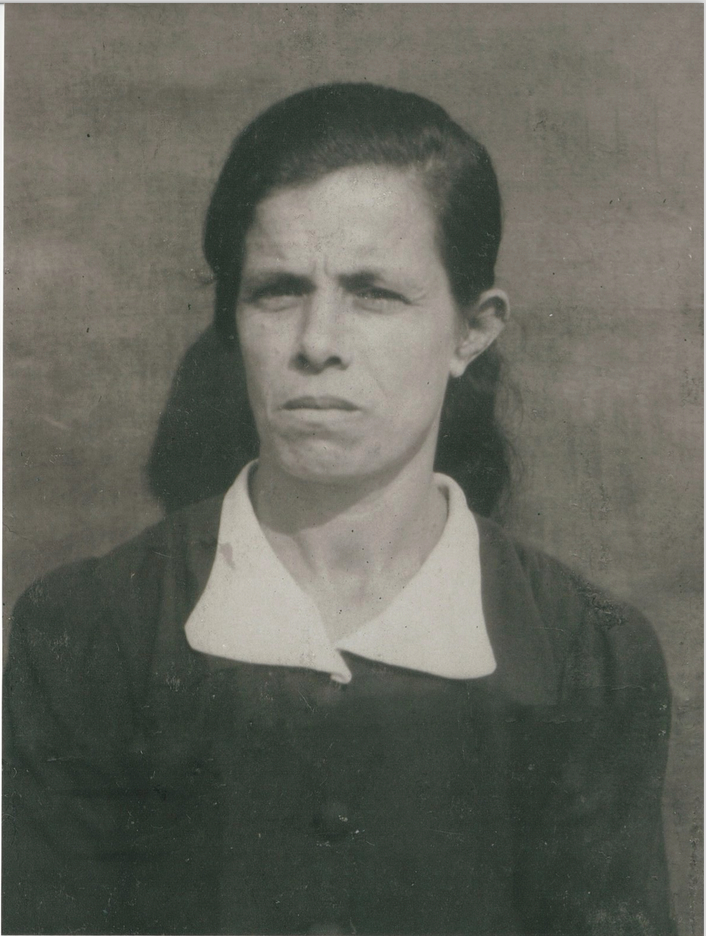

Teresa: A New Australian is dedicated to Deborah's nanna, Teresa (pictured).

Interviews

It was only after this initial research that I was ready to interview other members of the Maltese community who lived through this period of history. Researching Maltese history before conducting interviews felt more respectful to my interview subjects.

I approached the broader Maltese community through various associations and organisations, such as the Maltese Community Council of Victoria, Skola Maltija (Maltese Language School of NSW), and the Maltese Cultural Association of NSW. I also approached local community radio stations such as SBS radio, who had strong links to the community. After initial contact with interview subjects, I sent a list of questions so they would know what to expect in advance. This, I hoped, would put them at ease and allow them to think about their answers before we met.

The people I spoke with were incredibly generous and were often very humbled that someone wanted to tell their story. Over cake, many cups of tea, and the occasional tear, they told me stories of running from the bombings; of whole neighbourhoods being destroyed, of the dank, earthy caves; and of the minestra (soup) handed out by the nuns at the Victory Kitchens, which sometimes had goat meat prickled with hair. They remembered the long, rough sea crossings with bland food — but also the parties and friendships. They remembered arriving in Australia, full of hope and fear. They remembered the bullying, certainly, but what they remembered most was the peace and abundance that Australia offered.

These stories were the most valuable part in forming the characters and narrative that underpin the novel.

Additional research

Finally, I travelled to Malta, where I explored and photographed the cities, main battle sites, and caves, which allowed me to get a sense of the country, its people, and its architecture. This helped me add an authentic sense of place to the novel.

Bringing historical accounts to life

The end product of this historical inquiry is my novel Teresa: A New Australian. The novel begins in war-torn Malta, before Teresa and her family sail to Sydney for the promise of a brighter future. Teresa experiences terrible hardships in Australia, facing racist taunts from strangers on the street and kids at school, but she soon learns she has a valid place in her class and in her new country. Teresa’s story is a culmination of my own family’s story, and the story of the Maltese community who shared this experience — both those in Malta and those who migrated to Australia.

Historical fiction allows readers to consider various ethical concepts, values, and character traits of people throughout history. When I speak to children in schools about this book, I always ask about their heritage; finding a relationship between the content of books like Teresa and students’ personal lives can be the starting point for their own historical inquiries.

Conclusion

Teresa raises questions about Australia’s development as a nation, changing identity, ethics, and philosophy. It also provides an opportunity to look at how Australia dealt with migration as a nation after World War II, and encourages students to question how our country is dealing with similar issues today. It also provides a rich field to investigate the research that formed the novel and encourage children to carry out their own historical inquiry.

Image credits:

- Nanna Teresa. Image supplied by Deborah Abela.